Some Uncommon Poems and Versions

by Georg Trakl

Translated by James Reidel

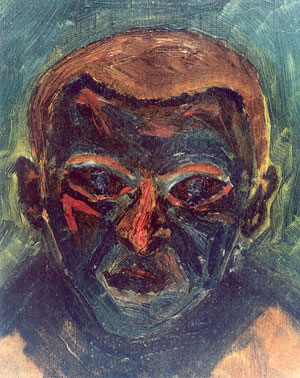

Georg Trakl, Self-Portrait, likely painted in the studio of Max von Esterle, Innsbruck, November 1913

Translator’s Note: The following selection is from my manuscript with the provisional title Our Trakl, which comprises three books translated from the works of the Austrian poet Georg Trakl (1887–1914). The endeavor is to mark the 2014 centenary of Trakl’s death and to show, as faithfully and felicitously as possible, why his work still matters, still lives after a hundred years.

His world and time, however, still seem very distant, especially for readers in the English-speaking world of the present. Trakl was born in late nineteenth-century Salzburg to Protestant bourgeois parents of Swabian and Czech ancestry. Trakl’s father was a prosperous hardware dealer and his mother a woman who decorated her home with fine antiques and, with it, those sensibilities of family pedigree.1 By the time Georg was born, his parents had a fine home and a little garden park for their six children, a French governess, and piano lessons for Georg’s gifted sister—and favorite—Margarete Jeanne Trakl (1891–1917), called “Grete.” Not only were they remarkably alike in being creative children, both shared a remarkable emotional and physical resemblance.

In boyhood Trakl was both intelligent and creative; however, he could also be withdrawn and even displayed suicidal tendencies. He was also sexually precocious and his biographers—as well as fabulists—believe he began sleeping with Grete during his adolescence and engaging prostitutes. It was during this time, too, that he became addicted to chloroform, morphine, veronal, and cocaine—all of which did not preclude his enjoyment of wine as well. Trakl, during his youth, also displayed signs of mental instability marked by his intensity of interests and passions. These and his bizarre speech and behavior have been attributed to schizophrenia. The diagnosis that I prefer, and one made at less of a historical distance, but also more believable and au courant, is that of Hans Asperger. He saw Trakl as an exemplar of the syndrome that bears Asperger’s name.

Despite the drugs and emotional disturbances, Trakl was incredibly well read, even disciplined and focused. In the early 1900s he began to produce a kind of lyric verse that revealed a full-blown literary talent, if not genius. While earning a certificate in pharmacology in Vienna, he began writing poems influenced by the French symbolists such as Charles Baudelaire and certainly their American inspiration, Edgar Allan Poe. In 1908, Trakl began to publish and, while under the mentorship of the Austrian editor Ludwig von Ficker, he became one of the leading members of the Expressionist movement in German language poetry. Many of Trakl’s poems were first published in von Ficker’s influential journal, Der Brenner, for Trakl and his work personified the decline and decadence of the old Hapsburg empire. Von Ficker also assisted Trakl in selecting the verses for Gedichte (Poems), published by Kurt Wolff in 1913. And while Trakl wrote his second book, Sebastian im Traum (Sebastian Dreaming), he received a stipend from Ludwig Wittgenstein, even though the philosopher admitted that what Trakl meant by his poems eluded him.

During these years of literary success, Trakl’s attachment to his sister Grete became a primary leitmotif and a source of crippling depressions. While she studied piano in Vienna, brother and sister likely resumed and finished the consummation of their incestuous relationship. Trakl, too, encouraged and facilitated his sister’s own drug addiction. Their close relationship, however, was interrupted by her relocation to Berlin to study music and her marriage to an older man.

The other great interruption—and disaster—in Trakl’s life was the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914. Obliged to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Army, Trakl joined his regiment as a pharmacist, a position that would keep him out of direct combat and supplied with drugs. In October, however, after a major engagement with the Russian Army near the Galician town of Grodek, a shortage of doctors and nurses forced Trakl into caring for a barn full of wounded men. Overwhelmed by his horrifically mutilated and screaming patients, and running out of precious drugs, Trakl attempted suicide. For this he was sent to a military hospital in Cracow for observation. There, while seemingly improving, Trakl wrote new poems and contemplated using his confinement productively. A telegram he sent Kurt Wolff requested proofs of Sebastian im Traum even though he had been told the book would be delayed indefinitely by the war.

Before receiving a response, Trakl was found dead from an overdose of cocaine tincture on November 3. And, as a sad and delayed coda to this tragedy, Grete Trakl shot herself three years later, in 1917, after a party in Berlin—this after admirers of her brother’s poetry had raised funds to pay his sister’s debts.

The overarching title for these renderings is to acknowledge the pervasive interest in Trakl and his influence on world poetry and on English poetry in particular. Trakl is canonical, something I can say given how many others have tried to translate his work. In that way he is ours, ours in a very personal sense. In my case, I came to Trakl in the late 1970s, when various translations were beginning to ripple through the poetry world to which I belonged. The most important of these was the chapbook by James Wright and Robert Bly, Twenty Poems by Georg Trakl (The Sixties Press, 1961). This ripple, however, goes back further to the postwar years, to other brief representative selections whose appearances parallel Trakl’s rediscovery in Germany and Austria.

So, he is our Trakl in that sense, in that we share him with these lands, readers, and the poets who were influenced by him, such as Thomas Bernhard, Ingeborg Bachmann, Paul Celan, Peter Handke, and others. And he is our Trakl in the way his work—and cautionary tale, too—is shared by friends. Again, in my case, it was with young poets, the late Daniel Simko and Franz Wright. The former, of course, gave us Autumn Sonata (1989), a selection of Trakl’s poetry that earned praise, and the latter still exhibits Trakl’s influence, especially in Wright’s late prose poems.

Following Simko, other selections followed and appeared in the new century, even a complete Trakl. What all these endeavors reveal, in addition to the undying interest in Trakl’s work, is that, like his contemporary, Rainer Maria Rilke, translating Trakl into English in some definitive way remains elusive. It is an industry of correction, refinement, reverse engineering, paraphrasing, and even some quite serendipitous misreadings. Indeed, translating him is like finding ones footing on the blue glass mountain of fairy tales—with Grete the princess within. The great irony, for me, is that the constant improvements, revisions, and corrections are in keeping with Trakl’s method, with all his obsessive autumns, black birds, neologisms—and in that same spirit—his Schwesterei, his sistering his poems, his madness, decay, and constant sense of downfall and sunset and the like. There is in Trakl a constant reworking, a constant revisit to the same forest, to see the same blue deer, and so on, to the same working poems to see them in the right light, or, more often, the right gloom.2

“All these versions,” I wrote Mudlark’s editor. “You can see in them how Trakl keeps trying to pick up a poem out of his experience and it just falls apart on him. So he tries once more. It is like they decay on him. All Verwesung.” And how do you translate that as you slip and fall to the bottom of Trakl’s blue glass mountain?

I have found that when you read Trakl in the original German, you get a snapshot of what is there. When you go back, you get another view. It may be sharper or less so, and with the feeling that it is intentionally less so. This can be frustrating for those who speak and think in English, that lawyer of languages. There is no fixed point to reading him or rendering him. This makes any book of translations simply a collection of snapshots of a particular reading at any point in time. Another way of rendering/reading a Trakl poem is through the barrel of a kaleidoscope, where one can only fix on a view when one stops or when the glass bits sometimes jam. I do this. But I have tried, too, to keep his diction and idioms in the past, where he liked to go, and I keep an eye on his time, too, an eye on his imperial world, while conscious of this country’s decline that in many ways resembles the old Hapsburg empire. So, I render Trakl as though he has a foot in our time, our history. I look for ways to both date and keep him strangely contemporary—as though he is anticipating our fate, too. The way he uses the ductile German word Geschlecht is very much a watchword here (and more obviously so in my greater collection of Trakl’s opus). It has many shades—meaning a people, a species, a strain, a race, gender and the organs that evince gender, and always with the implicit fate of procreation. Although Trakl seems not to be a social critic, he is. I even see in him a subversion of the progressive eugenics of his era as he chooses to redouble the strong, dominant, and lethal genes of a rot world in incest. In this, Trakl could almost rise to black comedy. There is no eternal recurrence in this very anti-Nietzschean poet save for eternally recurring Untergang—going down. Indeed, he anticipates our own demographic and declinist angst. And I could go on and on, recur in how he is Our Trakl, the poet of such a beautiful dead end.

— James Reidel

Cincinnati, January 2014

1 Synchronicity—here Trakl’s background resembles the American poet Weldon Kees, whose grandfather and father ran a hardware store and factory in Nebraska during this period, and whose mother was an amateur genealogist and a member of the D.A.R. Kees, of course, is the subject of my biography, Vanished Act: The Life and Work of Weldon Kees (2003).

2 It is why John Berryman’s elegy “Drugs Alcohol Little Sister” suffices for a thumbnail of Trakl.

Contents

Melancholie > Melancholy

In ein altes Stammbuch > In an Old Guest Book

Verwandlung > Metamorphosis

Kleines Konzert > Concertino

Menschheit > Mankind

Untergang > Going Down

An einen Frühverstorbenen > To One Short-Lived

Der Heilige > The Saint

St.-Peters-Friedhof > St. Peter’s Cemetery

Ermatten > Slackening

De Profundis > De Profundis

Märchen > Myth

An Angela > To Angela

Deliria / Delirium

Am Rand eines alten Brunnens > At the Edge of an Old Fountain

An Mauern hin > Along Walls

An Johanna > To Johanna

An Luzifer [Bitte] > To Lucifer [Please]

Nimm blauer Abend > Seize someone’s temple

JAMES REIDEL has published poems in many journals over the years and his new book of verse, Jim’s Book, is now available from Black Lawrence Press. He is the biographer of Weldon Kees. With Daniele Pantano, he has translated Rober Walser’s dramolets—short plays—selections from which appear in Conjunctions 60 (Spring 2013) and a forthcoming New Directions pamphlet. He has translated two novels by Werfel, including Pale Blue Ink in a Lady’s Hand and an expanded and revised translation of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, both published by David R. Godine in 2012. He has also translated two books of poems by Thomas Bernhard in one volume, In Hora Mortis/Under the Iron of the Moon, a 2006 selection in Princeton University Press’s Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation. He is currently finalizing Our Trakl, a three-book collection of the work of Georg Trakl to mark the centenary of the Austrian poet’s death in 1914.