Chants

Poems from Franz Werfel’s Judgment Day

Translated by James Reidel

These poems stand quite isolated in German literature.

—Curt von Faber du Faur

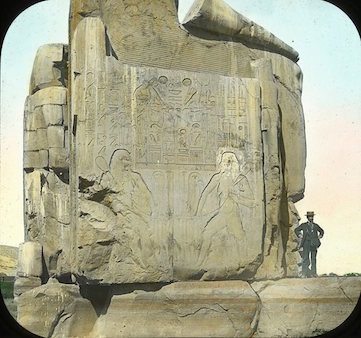

Tinted photograph of the Column of Memnon, early twentieth century

Translator’s Note: Chants (Gesänge) comprises part of a longer collection of poems, Judgment Day (1919) by Franz Werfel (1890–1945). Werfel is still a neglected figure, but he was once an imposing figure even in world literature and is still known for great (albeit conventional) novels such as The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (1933/tr. 1934) and The Song of Bernadette (1942) and strikingly gemlike outlier works, such as Pale Blue Ink in a Lady’s Hand (1940/tr. 2012). While his reputation has fallen into neglect, during his lifetime he enjoyed both critical and financial success. This too can be said of his poetry during the years just before and during World War I. Print runs of his books sold out. He read in theaters, to “packed houses,” reciting his verse in a declamatory style that had to be seen and heard. As a literary impresario in Vienna, he organized readings with such opening acts as the beautiful actress Billy Blei reading Robert Walser’s poems. Werfel had also admired the work of George Trakl, whose first book had been chosen by him for publication.

While Trakl (and Walser) could be said to be “known quantities” now, meaning their work is still discussed, still translated, and still meaningful a century later, the poet who towered over them is nowhere to be seen. And what relevance he had to such friends as Martin Buber and Franz Kafka will seem virtually unintelligible to modern readers, given our distance in time and place from this branch of early modernism. It will read to us as private, even occultish (Theosophical?) and too philosophically and mystically ambitious. Much of their strangeness comes from Werfel’s desire to be the rival, the foil of Nietzsche. Too, these poems also have a certain religiosity about them that seems well out of step with our time. That and all the negatives, however, are what attracted me to this “dead end” in a line of German Expressionism that is far too curious to leave behind.

So what is Werfel’s faith? Werfel was Jewish but considered Catholicism the superior faith, even though he himself never converted. The poems here, however, and many more, suggest a man reluctant to break his embrace from Mutterrecht (gone wild at times with prositutes and young girls). Werfel seems as much the crypto-pagan as he does a Catholic fellow traveler and a conflicted Jew, Red, public figure, and success, even as a stepfather. Werfel allows all faiths a place at his communion. To paraphrase his wife, Alma Mahler, in remarking about her ability to pray in more than one church, Werfel prayed in all of them, whether cathedrals, synagogues, temples, mosques, or pagan ruins (and for the latter, there was awe and reverence). His pantheon includes everyone from the Great Mother to the Devil. I have included a little appendix of these religious poems for the sake of further comparison.

The renderings here are both exploratory and provisional—in that middle realm between having it down on paper at last and a house of cards that is any translation. I have included notes to add some clarity and clues and to ameliorate Werfel’s strangeness to us—people he imagined, being an uncannily accurate futurist. (I recommend his last novel Star of the Unborn for further reading.) What I find worth reclaiming too from Werfel’s neglect is his relentless theme of self-deception and the self-flagellation that goes with it. There is something confessional about him and worth hearing if a translator and a reader are willing to be his priest, whether they have faith or none.

And lastly for now, I find these poems fascinating for their visions, all the reading behind them, the arcanum, how he knows all this stuff we have forgotten. They produce these hallucinatory incantations. Incredibly, Werfel seems more on drugs than his contemporary Trakl. In translation they reveal their daring, their innovation. And to follow Werfel, you must learn things you did not know, for he is encyclopedic in a way poets can rarely be again even with the great cheat of Wikipedia. There is, too, something sweetly sensual about his verse and sad, like the pathos he finds in his favorite prostitutes. And his mind ranged free like some child taken by an exotic adventure (he, like so many modern German geniuses, learned German from Karl May). It is that freedom, that wild up and down between Werfel’s heavens and hells, that makes him a pleasure, a forbidden one.

— James Reidel

Contents

Chants

Gesang der Memnons-Säule > Song of Memnon’s Column

Novembergesang > November Canto

Dezembergesang > December Canto

Fragment der Eurydike > Fragment of Eurydice

Der Ruf > The Call

Verlust > Loss

Vergessen > Forgetting

An Eine Lerche > To a Skylark

Trinklied > Drinking Song

A little appendix: Werfel as a man of what faith?

Der Tempel > The Temple

Absalom > Absalom

Gewaltige Mutter > Almighty Mother

Schuld > Guilt

Müdigkeit > Weariness

Der Gerichtsherr > The Magistrate

Der Widder > The Ram

JAMES REIDEL has published poems in many journals over the years and his new book of verse, Jim’s Book, is now available from Black Lawrence Press. He is the biographer of Weldon Kees. With Daniele Pantano, he has translated Rober Walser’s dramolets—short plays—selections from which appear in Conjunctions 60 (Spring 2013) and a forthcoming New Directions pamphlet. He has translated two novels by Werfel, including Pale Blue Ink in a Lady’s Hand and an expanded and revised translation of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, both published by David R. Godine in 2012. He has also translated two books of poems by Thomas Bernhard in one volume, In Hora Mortis/Under the Iron of the Moon, a 2006 selection in Princeton University Press’s Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation. He is currently finalizing Our Trakl, a three-book collection of the work of Georg Trakl to mark the centenary of the Austrian poet’s death in 1914.