A Requiem of Hammers

Poems by Adam Tavel

Creation Myth | Catafalque | The Sons and Daughters of Unimpeachable Light

At the National Gallery | Gauguin’s Teeth | Comrade Holmes | Adam’s Apocrypha

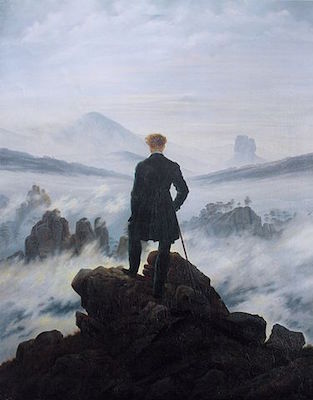

Creation Myth

Caspar David Friedrich, The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818, oil on canvas, 98x74 cm, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany

Drunk on mead and the drone of chanting, our soothsayer rained incense and gibberish on our chieftain’s crimson sprawl. His widow smothered herself with snatched-down clouds and I marked the snarls blooming on her sons’ beardless mouths who, in their minds, had already left to barter with the blacksmith. Indifferent, our best warriors in darkness sculpted their revenge. When prayer drove the dampest eyes to the mountain where our gods reside I saw only mountain, butcher birds circling carrion, a smear of mist colorless as my hovel. Bound to ewes, it’s no wonder we believed our people rose from clay and sanctified dirt by scratching with staffs. That night I stuffed my blizzard fur inside father’s shield before feasting with our galled, milk-eyed mongrel whom I tethered for my sister to slow her morning’s river walk. She knew any scrap bone broke his begging. She knew to tell her elders that my mud-tracks led up to mist and disappeared.

Note: “Creation Myth” is a tribal retelling of David Caspar Friedrich’s famous Romantic painting The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.

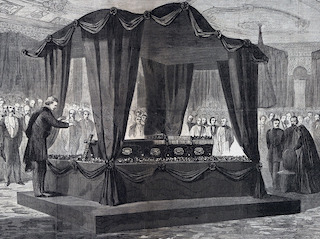

Catafalque

President Lincoln’s Funeral Service at the White House, April 19, 1865, engraving from Harper’s Weekly Magazine, May 6, 1865

Two tube-top bimbos nuzzle Barry Winter, the mattress king of Crisfield. His goatee glue shimmers in the blinding snow-light as he shouts his only line: fourscore it all must go! The prices pulsing make a red extravaganza of February curbs. He bounces an unsheeted king, top hat tight to his bald spot with a chinstrap, his costume frock coat two sizes small. It’s so cold in the take that airs hourly I can see the areolas of both girls puffed up through spandex. According to my cousin who lost his shirt running the sub shop next door both girls are Winter’s nieces. |

The First Lady’s mewling melted walls and rushed our hushed deliberations on which pallbearer should lead Lincoln down the hall. Wordless, harried, we shed our brogans, our stocking feet a squeakless glide to spare her hearing what yonder passed her door. We carried cumulus and sky shimmering on the casket lid with the rigid Ls of our arms numb across the lawn. I swear though back-soaked we could not breathe out our mouths for grief of what might pass through. Beyond, the labored platform with its nightmare canopy was a requiem of hammers. |

Note: “Catafalque” was inspired by a journalistic sketch of Lincoln’s catafalque from 1865. The anecdote about Lincoln’s pallbearers taking their shoes off when they removed his casket from the White House to avoid upsetting Mrs. Lincoln is factual and can be read in Thomas J. Craughwell’s Stealing Lincoln’s Body. The engraving of Lincoln’s Funeral Service at the White House, from Harper’s Weekly Magazine, can be found, using The Civil War Research Engine, in The House Divided Project at Dickinson College, Carlisle PA.

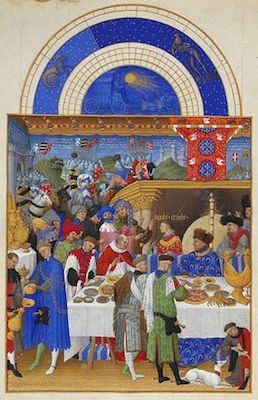

The Sons and Daughters of Unimpeachable Light

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Limbourg Brothers, French Gothic manuscript illumination, 1412-1416, Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

We planted lilies in our chamber pots and watched them bloom October in the heated greenhouse. After rains we drained our brandies there, voyeurs among the greasy kingdom of slugs. No skein of fog could ravel our spirits—we were the sons and daughters of unimpeachable light, free from the creaking wheels of carriages, the city’s devastating stench, the rats who bobbed on bones in the gutter’s current. Once a month we granted audience to ruddy serfs whose babes refused to suck, who woke at dawn to gawk at maggots wreathed around a heifer’s anus. Each turd we called dear sir. They’d slouch and fret and spin their hats awaiting wonderwork. How dreadful, we said, passing chalices brimmed with sorbet. We recited sympathies. We raised our rubied fists to brace our yawns.

Note: “The Sons and Daughters of Unimpeachable Light” satirizes the Limbourg Brothers’ Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The page displayed here, Janvier, is from “Labors of the Months,” the section illustrating the various activities undertaken by the Duke’s court and his peasants according to the month of the year.

At the National Gallery

for Ellen Hathaway

Pietro Tacca, The Pistoia Crucifix, c. 1600/1616, bronze, corpus 86.9x79x20.6 cm, cross 167x90.1 cm National Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Another sooty crucifix leers and leans, angled on slackened cables anchored in the ceiling. Baroque, gargantuan, its bronze charred lusterless by centuries, it slows no steps but mine in this fountain room’s cavernous tinkling where I try and fail to pucker out the slurring vowels of the Pistoian master’s name. The agonized gaze of Christ leads fifteen yards away to the kneeling girl who keeps giggling as she flips pennies from her palm into the perpetual marble roar of a lion jet. Twin transmitters from cochlear implants shimmer in her tawny hair like flying saucers smashed in a wheat field. Each time she leans her face closer to the rippling surface to mark the spot a twirler fell her grin glows orange above a shallow copper sea. The centurion’s gash takes a squinting stare to spot amid exaggerated ribs. A child might say the wound had healed. A child might stretch to kiss the frozen mane.

Note: “At the National Gallery” references a lion fountain and Florentine crucifix, both of which are located at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Regrettably, the lion fountain lacks an online image.

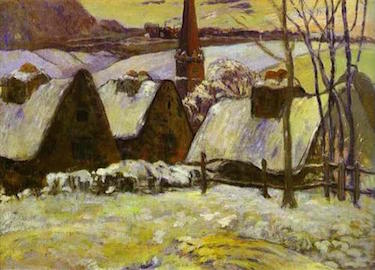

Gauguin’s Teeth

Hiva Oa, Marquesas Islands, 1903

Paul Gauguin, Breton Village Under Snow, 1894, oil on canvas, 62x87 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Two Atuona boys delighted in stomping his Maison du Jouir, his filthy little hut, until the pale bellies of its roof thatches shriveled in the sun. Their sisters’ nipples whorled purpura through the smoke on every canvas burning except the snow- cloaked steeple back in France, which they left leaning against a shaded stump to sell to homesick sailors. I made excuses to pass his well and waste my hours there, straining for the faint glint of ferrules from busted brushes on the bottom. Only so deep and no further, the mottled light caught the mouth of the beer bottle that held four black teeth—teeth that once scraped my neck and later I helped him yank through a drunken fog so thick we roared each time he spat out blood. So deep. My belly’s shriveled hut. The day he clanked that bottle down he found my black hair smeared across the milky breast of a mountainside and left it.

Note: “Gauguin’s Teeth” alludes to Breton Village Under Snow as well as recent news reports that some of the painter’s teeth have been found in a bottle at the bottom of a well. The poem is in the voice of a teenage Tahitian lover, of which Gauguin had many.

Comrade Holmes

for Lienna Hillenburg

How strange to hear the Russian river out of Livanov. His gaunt and hawkish face broods, snug inside its deerstalker, beside a pool of blood so obviously fake I shake the spell of cinema and pout at the scene’s poverty. And yet such grace— the magnifying glass, unseen, now glides beyond his houndstooth inverness cape. Your Sherlock peers unflinchingly at clues so lost upon Lestrade and Watson, mute as children at a magic show, that I’m absorbed again. Our realms converge tonight: the pilfered ring, the smog that parts like hair, a cane’s faint tap across the thoroughfare.

Note: “Comrade Holmes” responds to the Russian made-for-television films and corresponding Moscow statue of Sherlock Holmes as portrayed by Vasily Livanov. The photograph, displayed here, of the statue by Andrey Orlov is from Tumblr. It includes Doctor Watson as portrayed by Vitaly Solomin. The statue is located on the Smolenskaya embankment alongside the Embassy of the United Kingdom in Moscow.

Adam’s Apocrypha

Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490-1510, oil on oak panels, 220x389 cm, Mueseo del Prado, Madrid

We heard some voice proclaim the dawn was ours. That drizzle drove the bloom. Menageries of all that stalked and crawled belonged to us. We beamed, tracing one another’s ribs. The legless one stuck his tongue through hours beneath the danger-fruit that set us free to suffer sums. His opalescent fuss meandered on the mottled rinds and slipped in rot we knew was there. Though mute and tame we willed his voice to barter with our shame. But then the desert too, its mutts and stones howled to haunt our blistered nights. Our same and tender hands sparked hard at flint. Alone we learned the shadow voices were our own.

Note: “Adam’s Apocrypha” is in conversation with Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Adam Tavel won the Permafrost Book Prize for Plash & Levitation (University of Alaska Press, 2015). He is also the author of The Fawn Abyss (Salmon Poetry, forthcoming) and the chapbook Red Flag Up (Kattywompus, 2013). Tavel won the 2010 Robert Frost Award and his recent poems appear in Beloit Poetry Journal, Sycamore Review, Passages North, The Journal, Potomac Review, and American Literary Review, among other places. He can be found online at adamtavel.com.