Mudlark Poster No. 115 (2014)

Four Poems by Jenny Molberg

Nocturne for the Elephant | The Dream, The Sleeping Gypsy

The Pheasant | The Muse, Posing as Maria

Nocturne for the Elephant

In the upper menagerie at Exeter Change, where walls are striped with iron cages, a musician sits down at his piano forte to play a nocturne for the animals. To him, the audience is familiar, each a different beast, and each in its prison. Adagio, he plays, and when his hands spill down the scale, the Indian elephant tilts the broad leaves of its ears forward; tusks blunder against bars as ivory keys prod wooden hammers, felt-covered, like the animal’s ancient tread on desert soil. The song is a downpour and the elephant begins to pace. The pianist drops to the low b flat and, in the base of its throat, the elephant echoes the tone—dirge for a time when, head bowed, he plodded into a pond, tube of his trunk sloped in milky water, lifting the drink to his mouth, roping the trunk to drench the ashen body, each wet-darkened foot lifting, stirring, a vibrato of water emitting, from the body, watery rings which enclosed him, then disappeared.

Note: Written in response to an article about the pianist and the elephant, On the Difference of Structure between the Human Membrana Tympani and That of the Elephant, by Everard Home, published in 1823 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

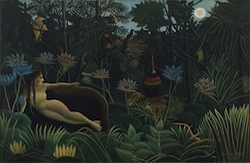

The Dream, The Sleeping Gypsy

Henri Rosseau, The Dream, 1910, and The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897, MoMA, New York

In what would be his last work Henri Rousseau painted a moon in place of the sun, passive as a dying woman. What is light are the girl’s breasts, two bright pomelos, the orbed voyeuristic eyes of the lioness, the trees’ orange fruit, the bird’s yellow wig of feathers. My mother’s skin, artless, her hands deft as she turned each page, whispering the names of paintings, recognizing in Rousseau not the childlike lines or the misunderstanding of a world so different from his: world of flat, vague skies, but his layering and layering, spreading a strange, unutterable music onto the canvas, slow as the acacia that rings its own grain as the years pass. In the other painting, the one we especially loved, a woman asleep beside her gourd-like lute, a few incisions of light in the desert sky, her long sleeping hair, and again, the lion beside her. The moon’s face a cold white god. This is the metastasizing beauty of my mother. My mother the gypsy. I, the pinpricked sky. The lion her cancer.

The Pheasant

... the variety of monsters will be found to be infinite.

— John Hunter, “An Account of an Extraordinary Pheasant,”

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1780

I. For eleven springs against the April snow, the spots on her feathers were black eyes, the thin reeds of grass lashes, and she hunched and cooed as the bright male beat his wings against her, bobbed his necklaced neck like a ship’s gilded bow, held her head with his beak and curled his tail feathers around her body. The pheasant came to the woman each morning for food, and each year, presented her with a small brood of chicks. The woman began to see herself in the bird—the way she pecked and rounded up her young; her subtle beauty, dulled like tinted paint and the way she curtsied before the glamorous male, who, almost refined, tucked her beneath him. II. This year, after molting, the pheasant is no longer egg-colored, but deep golden red, her long truss of feathers low to the ground on her small frame. Her spots not eyes, but sapphires, and the long cleft of her tail cleaves the sky into two skies. The woman calls in the scientists and they pin down the bird with gloved hands. They prod beneath the spectral plumage. They pluck and hypothesize and write things down in notebooks. The colors of her are fire, imperious against the pale wood table, the humbled white of the snow.

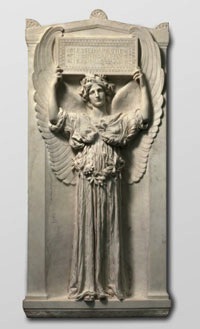

The Muse, Posing as Maria

For her father, the sculpture represented Maria Mitchell’s singularly sweet and blameless life. — Philadelphia Museum of Art, on Saint-Gaudens’ The Angel of Purity

But there is always more to it. The muse, the sculptor’s mistress: her stone-kept pout, plummet of the neck, the yawning eyes. And Maria. Dead, diphtheria, age twenty-two, never married. The muse, his whore, but alive in a body not made of stone. And the stone, too, carried up from the quarry, and what he cut away. The two of us stand before the sculpture a century after. You turn and say, you’re not who I thought you were. What about before, I say, when it was different? You say, she is beautiful. I say, why, thinking her hooded eyes, the palms’ flesh like white plums, the ruched wings. Outside, the wind is strong enough to carve ice. Outside, the girl I once was shoulders the cold.

Jenny Molberg, a Texas native, earned her MFA at American University. Her poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in The New Guard, Louisville Review, Mississippi Review, Third Coast, North American Review and others. She is a teaching fellow and a PhD candidate at the University of North Texas, where she is the managing editor at American Literary Review.