|

Five Poems by Erin Lambert

Koudelka’s Turtle | Carnival: A Study of Two Sisters | Debut | Forgiven Erin Lambert is the author of RESOLUTION, forthcoming in November 2008 from Finishing Line Press. Her poetry has appeared in Mudlark before, Poster No. 44 (2003), and in many other journals too, such as Blackbird and Conjunctions. She is currently an assistant professor in the School of Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication at James Madison University.

after Josef Koudelka’s photograph, Turkey, 1984 One could find them as sincere as the edge of the river where the water bends, then recedes into earth as the night into the distance. But when I find the compositions cruel, I also remember you, Koudelka, behind the lens where, I tell myself, you staged coincidence. Still, you are not here, not with me by this river where the sparrows bathe each morning, though you have lived in poor towns like this one where so many despair, afraid everything they’ve come to matters as much as these sparrows, will be remembered as often as the land by the water. Which, in either case, is to say not enough, but one must see things as a tree to understand the land has always been something taken — by elements, by empires, and by the very people fleeing both — but only the grass and this morning’s air can hold the value of a sparrow. These things I keep in mind when I consider your photograph of a turtle on its back, legs stretched desperately into day, and gazing up a rocky incline the way I saw several people in Sienna stare up at Saint Catherine’s head; it was severed to rest as a relic on a white silk pillow, and she appeared menaced in death as if her final thought had been of a toothache. How each person petitioned her to relieve him of the hole he labored to mend. Like them, your turtle stares at the slope of the hill when its conflict is in its position; the weight on its back will only help to keep it down. I once told myself that after taking this picture, you gently rearranged the turtle’s composition until it lay across the incline where it could grasp enough momentum to change its own perspective. Then, given the loose terrain, I could see after just a few steps, it would have slipped and rolled onto its back again, prostrate to the open air as if giving up each kick to encourage a predator. So, I thought, you may have had a point of keeping everything as you found it. Then, years later, long after leaving that turtle upside down, perhaps when winding back the film in the very same camera, you realized nothing remains untouched, not even the head of a saint still harboring her final vision. But no, Koudelka. You did not. You are not one who waits to see anything, which is why, after taking this photograph, you turned that turtle over and carried it with you a meter or so beyond the edge of the incline until the ground became soft with leaves where you set it down. You knew once it sensed itself level and unrestrained, it would release its vision from its shell and crawl away from that hill; just as you knew to look upon this world, to see it as it is, is to change it, enough to let it go. Carnival: A Study of Two Sisters

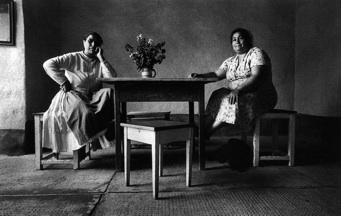

after Josef Koudelka’s photograph, Moravie, 1968 Derived from the removal of meat, carnelevare, it also means Moravie 1968, where two sisters are seated at a simple wooden table, its emptiness spread before them as an absent feast. Maruska, her elbow on the table and fist on her hip, would like to pull the trigger. She knows this much, and since she has known for quite some time, her faint grin never falls away, even when peeling an onion. But her younger sister, Mila, who leans to the right, would like to persuade her to poison. When she mentions her calculations — how long it will take the crushed holly to dissolve — she flushes, her pulse becomes erratic, and a glow emerges from the heavy lines in her palms. She’s a small woman with a limp, who rotates her left hand clockwise over her right knee, habitually reaching for its pain, and believes she knows the better way. Though she cannot bring herself to name it, Maruska hears in Mila’s movements each vital turn of her own life slip into the damp courtyard below. So a pall spreads between them like a coffee stain, these sisters who share the same desire for a man and an unresolved scheme for how best to take care of him. § I must admit none of this is accurate. The man is already gone. He sat here once with Maruska before those yellow marigolds wilted in their bowl, but he meant his love much less than a silk shawl, which is to say it was as inevitable and as permanent as breeze or dust. For if we look closely, and we must, there is still some movement in the mirror above Maruska’s head which means to turn our attention outside of the frame and lead us down several sparse roads to Mikulov. As if the man’s departure were fixed there to hang over Maruska as a thick, flecked aura of loss, the way so many empty chambers become dispersed through dough, then preserved in bread. Turn away from this. It is too sad to consider as it is still too much for Maruska to remember. Which is why she joins her little sister to partake in the absence of their shared feast at this simple table in Moravie, holding a grin in place of a gun as that red dog, crouching (almost imperceptibly) by Mila, licks the short, dry arc of Maruska’s shadow. We, who have inherited all things named after the weight of disappointment by the strained voice that troubles winter, once stumbled onto sleep we thought sound for the hope we held would soon awaken. Even water knew what propels us would not lie in our wake, that long white haze of ‘has been’ gone by; just as tomorrow’s skies will foster doubt, peer into each terror stalking our minds, unaware of the glory they are said to contain. In the end we could choose to forgive even this if only to leave our blameful, broken cities by way of wind above the sounds of foo and mür as one breath, sealed within three cadences of rain on wooden steps down familiar streets of soft departure. § That we will see the stranger was ourselves is not for me to say, but I can say everyone’s solitude will be undressed at that moment until we are without regrets or one haunting grief in which we believe we pushed anyone — ever — away. Easy, then, to loose the reins that dragged our mules of violations over pocked, unforgiving landscapes because we find what we have always been: without a stone. Perhaps we may stand together in silence before letting each mistaken thought of separation pass, and make our debut as a story of the sun and a ring of violet clouds over a bridge of starlight where nothing — unlike the countless scripts for fallen lives that play themselves cruelly forgotten — could possibly be tragic once the cells are empty, and the warden and the criminal, together, go home. For we know should we believe again in failure or in shame, that fitful sleep will still be temporary as all deceit and every beginning of this world. Those fortunate to witness how water brings itself to an end in the golden sheen scrawled through the center of a river — in even the green aura of ailanthus — may recognize the legends contained therein of every minor prophet to come; and those who lose everything ever trusted & known, & just when desperation comes to clear its throat, look up into the worn down branches of winter (where all things are as blue silk & silver stitching) to see soon what comes will hold in place the nest & the leaf, will also find in this delicate fabric why the willow drew the map to all migration: to hear the gentle diction of mercy born itself beyond our shallow clearings, beyond husk & stone. A Letter to Nietzsche & the Committee We could exist one hundred, forty-seven years in service, but this committee would still manage to say nothing. And if, as Nietzsche gleaned from the irrational gulf between blame and regret, we can only experience ourselves, then I am also writing to inform you of my immediate need to be excused indefinitely before a contract is drawn and conferment of a title begins. Because I cannot comply with policy; I still believe in a shared ligature of minds, the possible light of unanimity. Point being, I understand that you, Mr. Nietzsche, were speaking of perception, that life is in the mind but we have infected ourselves with ego: that zephyr, which carries distinction and alienation, is consumptive. Even you, sweet unknowable Sir, crumbled in its pocket. So I ask that we may create a new mindset fashioned after the polite agreements between frost and glass, at least study the mediation of rain. There could be one thought by which we cease all accusations, another to relinquish contempt for the unexplained; for it is we who turn our fields fallow and bring every root release from the dirt’s memories of drought and wars. So I implore you, Fellow Committee Members: See here, the hands by which all is made forgiven; here, the sky unburdened, now possible and here, the sparrow and the threshold. Acknowledgment: The Josef Koudelka photographs, Turkey, 1984 and Moravie, 1968 are from JOSEF KOUDELKA, published by Thames and Hudson in their Photofile Series, New York, 2007.

|