Empire Ekphrasis | Poems

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Author’s Note: In this series of poems, I see works of art and music through the filter of imperial history and I attempt to find contrasts between the impression of indulgence reflected in an empire’s sensibility and its paucity of connection with the larger beauty and spirit of ordinary life. While art may boast and boost the power of an empire, and empire may afford (some) artists the luxury to indulge in art for art’s sake, the history surrounding the aesthetic language of empire, especially the history of oppression, resides in it permanently as a haunting presence. — SZH

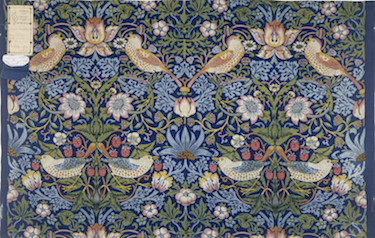

Strawberry Thief Singing

William Morris, Strawberry Thief (textile design)

The thrush, caught jubilant, after stealing ripe fruit from the artist’s garden, goes to a prison of textile, serves a sentence of centuries in cotton, needles passing through her feathers, stitches on the sigh (or the ghost of song) in her bill, on wings. She will be stretched on Raj furniture across the commonwealth, a souvenir in chintz, her crime displayed on bedspreads. She will hang from windows, a doll of the wind.

A Prince and his Falcon

A Mughal Prince with his Falcon,

India, Mughal Empire, circa 1600-1605

The Mughal brushstroke is thirsty for hunt. Mares, moonlit steppes, skull heaps, coils of Mongol destiny come back as Indian henna tendrils, geese, cheetahs, antelopes embroidered on a prince’s tunic, sword sweating falsities tied with a brocade sash. The prince, vacuous, the shape of a question, the falcon, impenetrable; its metallic gaze humiliating, golden tassels wrapped around its leather perch, plumage full, mass of unbidden history.

The Four Horns in the Afternoon of a Faun,

Claude Debussy, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune,

after Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem of the same name

two bassoons, three flutes, two harps, oboes. Plus the heat of strings at midday, cirrus, that squirrel-colored wisp of cloud curling around the faun, leaves nothing to chance: each blade of grass is art-hungry, upturned to receive a dewy gem fattened by slender nymphs. A man, golden as goat, beast of meadows, a climber who shears innocence to fabricate innocence, goes on crowning himself, girdled by dream.

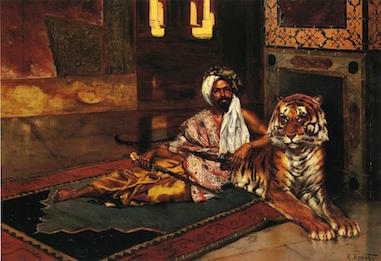

The Sheikh and the Tiger

having just offered prayers

Rudolph Ernst, Sheikh with the Tiger

sprawl on the cavernous, velvety shelf of the Orientalist’s fantasy. There are no charmed constrictors, lutes or water-pipes snaking between empire and voyeur, but a curious Sheikh with skin a shade less copper than the tiger, both beast and beast stretched in ultimate luxury on the prayer carpet. The sheikh in diaphanous silk has somehow exited the sacred moment with one arm bare, muscular, sinister—etched in the future.

The Awakening Conscience

swaddled in red chintz

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience

panics, rises from empire’s lap, finds you, dear viewer, between her clasped hands, and you, doused in cold sweat, have only a mirror behind her to show you light from the window ghosting through trellis and tree. Time, in sudden primal shame, stands naked under a glass dome on the blustery piano. She steadies herself, feet between empire’s limp glove and the spasm of wings—the feline grasp unlocked. Window: a giddy call echoed by mirror.

Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s poetry has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Poetry International, The Cortland Review, Vallum, Nimrod, Atlanta Review, POEM, The Bitter Oleander, Rhino, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, Hubbub, Spillway, The Adirondack Review, Drunken Boat, Split this Rock! Himal, and other journals worldwide. She has taught in the MFA program at San Diego State University as a writer-in-residence and is the recipient of the San Diego Book Award, Nazim Hikmet Poetry Prize, SAARC medal for Literature, and Stout Award. Her work has been translated into Spanish and Urdu.