Laurence O’Dwyer

from The Lighthouse Journal

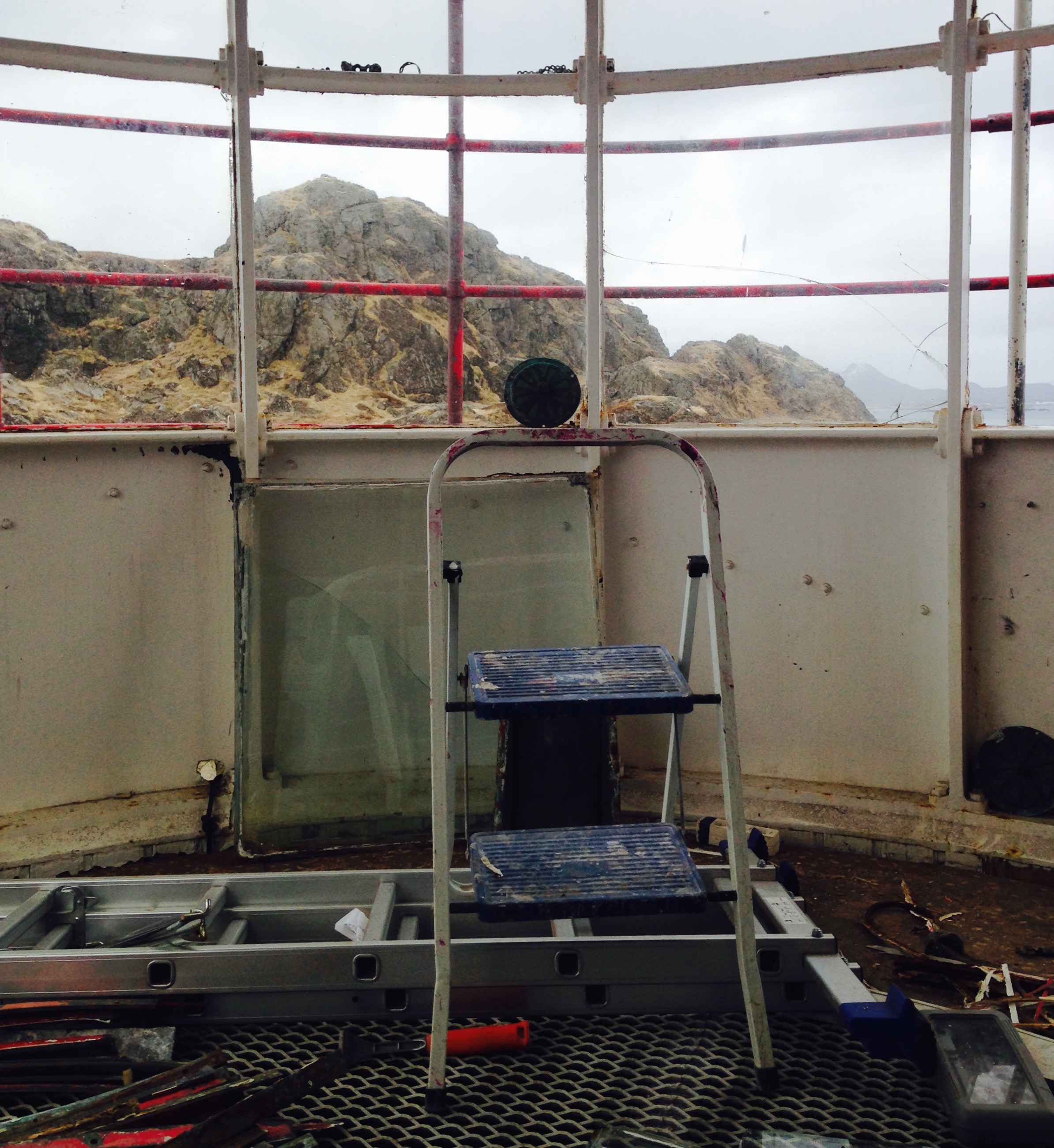

In the Tower, Photo by Laurence O’Dwyer

Editor’s Note: Laurence O’Dwyer’s second collection, The Lighthouse Journal, will be launched on Culture Night 2020 (Ireland) — September 18th — in cooperation with the Clonmel Junction Arts Festival and supported by Tipperary County Council Arts Office.

More information about the multimedia launch can be found HERE.

Tickets for this event may be reserved HERE.

The Lighthouse Journal is an ode on the future of Litløy, a small remote island located six miles from the Norwegian coast and one hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle. It is narrated via the camaraderie of manual labour during restoration of the lighthouse which was originally built in 1912.

The multimedia launch showcases The Lighthouse Journal with an interactive app created by Malte Olsson (Macalaus Studios) and features narrated poems, music, maps, photography and video footage from regions of Vesterålen and Lofoten. Accompanying the app is a short film with narration of the poems by Donal Gallagher (Asylum Productions); both app and film were commissioned by Tipperary County Council Arts Office

Selections from The Lighthouse Journal have been published in Poetry Ireland Review, The North (UK), Mudlark (USA), Chaleur (USA) and Cyphers (Ireland). Other distinctions include the Yeovil Poetry Prize, a nomination for a Pushcart Prize (USA) and publication in translation in Norway’s oldest literary journal Vinduet.

Contents

Occupation

Occupation

My First Norwegian Peak

My First Norwegian Peak

By the Lighthouse Door

By the Lighthouse Door

Dynamite

Dynamite

Slack Line Music

Slack Line Music

Barbed Wire

Barbed Wire

Si Phan Don

Si Phan Don

Occupation

Kink and twist, we fish in rubble,

pulling at the tail end of more barbed wire

until it snaps and sunders with a puff.

Red dust like a magic trick: the invasion

of Poland. Hindenburg asleep. I prune

while Julien saws. Down at the boathouse,

a mountain range of plates rises from the sink.

Max is reading a paper about avalanche research.

The pier outside is stacked with trays of glass.

I’m not sure how much weight the boat can take.

We’ll find out tomorrow when we bring it all —

glass and wire — to the recycling centre.

Seven decades after the fact — maybe we could ask

the Chancellor for a little help, a subsidy perhaps

for decommissioning German memorabilia.

I use a hook to pull the trays. The wicker baskets

we take down the steps in pairs. I ask Julien for

a rest at the switch-back. My muscles are burning.

Work done, he goes back to the tower to do a little

sanding of the wooden slats, the wainscoting.

What he always does when he’s tired and needs

a rest from heavy lifting. In Understanding Wood,

Hoadley describes rift grain as occurring at an angle

between forty-five and ninety degrees to the surface.

He calls the definition of the Woodwork Institute

‘bastard sawn’. It is a language I love, lamellophone:

a go-devil, a splitting maul, the oft confused quarter-sawn

with cambium flecks and medullary rays that no rift-sawn

wood can rival. I could go on forever or at least

until the buzz-saw nearly has my own hand cut off.

§

After the two boys had gone to bed last night;

I went to the deck to brush my teeth, thinking

— or maybe I said aloud — Do they ever get tired?

I meant the seagulls and their wheeling caw,

eternally sea-sick. Their nausea comes

from the Greek word for a ship.

But there were no ships in the bay last night,

no Odysseus coming from the waves

to surprise a beautiful Nausicaä. I spat

a mouthful of toothpaste onto the rocks.

The way gulls foul sea-cliffs with guano.

The moon was rising over Lofoten.

I thought of soldiers unloading that barbed

wire for the first time. New as bales of hay.

I bet one of them returned to Frankfurt

where he worked as a chemist, playing

the violin in his spare time. He forgets

the name of the lighthouse keeper’s wife,

her nod as he stands on the pier.

In the morning, Julien’s up and at it —

doing his damnedest to get tetanus

with splinters and wood and fire.

The sink in the boathouse is piled higher

with dirty dishes while Max takes the stove

apart trying to fix the spark of the burner.

The knob of the ring is broken.

We use a dinosaur egg to keep it pressed.

An elegant safety feature — how a stove

senses the conductivity of a flame.

The combustion of gas releases a sufficient

number of electrons to support a current.

An electric circuit thus starts or stops

the igniter, based on whether or not the flame

is lit. Max would have known all this. I didn’t.

I wished he wouldn’t fix everything.

I liked using that egg; was sad to see

it’s legend disappear, even if it was just

a smooth, round stone. The click of the auto-

ignition — the flame, the burn — burner of ships —

wasn’t that the origin of Nausicaä’s name?

My First Norwegian Peak

White wake. Wind-slap.

Speed. The boat is filled

with buckets and trays

of broken glass, long

protruding shards touch

the ribs of the frame

that’s inflated and rigid

with air. The glass seems

to smile at the danger

of so many blades.

Restless and nervous,

the eye shoots out

to Lofoten as we narrow

to the pier. Once moored,

we lift and haul and swing.

Then drive the load

to the recycling center.

Work done, Max drops

me by the roundabout

at Straume. Down the road,

a dry-stone wall borders

a field where a farmer

leans on a shovel. I nod

and ask about the summit.

He points to an antenna

round the corner. No English,

but sound and semaphore

are clear. Up there, turn right.

Something about a false

summit, a ridge that he draws

with a flourish of the hand.

I wave my thanks and carry on

round the corner, over a fence,

through brambles and lichen

that disappear under snow.

It steepens and brightens

to a peak that floats high

above the water with an airy

drop to a horseshoe bay below.

Out in the ocean, Litløy —

our island home — is crouched

behind Gaukværøy.

It seems there should be

some protocol, some shaking

of hands before the survey

of the interior and the ocean,

but everything sings from

its core, precisely because

there’s no contract. The blue

dances of its own accord.

The snow gleams with wavelets

beyond our ability to see.

The green in the valley

is blurred by so many mirrors

of blue. Scrambling down

takes half the time

of climbing up. I make it

to the roundabout. Put out

my thumb. The third car stops.

Greire. He’s from the south

but every summer his parents

brought him to the north.

Last year, he decided

to move for good.

He’s on his way home

from an interview

for the job of janitor

at the local school.

For now, he works

at the hardware store.

He says he’s happy. There’s no rush.

He loves the land, the silence.

Then he adds — you’re from Ireland.

He’d picked up Max the week

before — that’s how news travels

up here. Max being Max he was

hitching with a pair of skis.

He’d told Geire about a new

arrival. If you want to hide —

the worst place to go would be

the Arctic. The more the land

resembles a vanishing point,

the clearer our whereabouts become.

He drops me at the pier.

There’s a bench by a cabin,

red and rusting with a window

that lets no light in.

I’m alone for the first time

since I arrived. I open

a can of beer.

That’s the miracle

and the paradox of living

on a deserted island.

It’s the busiest place I’ve been.

Labouring on the lighthouse

has squeezed us like oranges;

peeled and torn and pressed

to the last drop. When Max

returns I notice that his jacket

looks like an old banana peel.

On our way home, the boat

is as buoyant as cork, lighter

by several hundred stone.

A few shards of glass remain,

a few beads of quartz, devoid

of any danger. The speed picks up.

Sea spray cuts but does no harm.

By the Lighthouse Door

What is the Norwegian for download?

Julien rocks back and forth with his laptop

propped on the súgán beside the stove.

To count each lap from pier to summit,

I set a stone by the lighthouse door.

Lightheaded, I pitch myself down the helix

that winds round the base of the tower,

leaping, two steps at a time, pulling

on ligament and bone — counter-tiller —

more like freefall than running, a plumb-

line torques all the way to the final leap

and bound that plants me on the runway

of the pier. Now slap on the brakes,

kick the boat — turn-around — back up.

Half-way through this ritual, I take

a bucket and fetch some water

for the stove. Bending down, I bobble

and panic as a wave swallows

the last steps of the pier. Unsteady scoop,

I yank the rope — green with algae — steady

the fear. The rings that pierce the snout

of the wall draw tight — now slack.

I haul the bucket up to the boathouse,

shaking and wobbling — briny star-melt,

eons old, spills and sizzles on the stove.

Thirteen, fourteen, fifteen stones. Atrium

peaked and capped. I place the final stone

and am ready for one last freefall, sailing

all the way to the boathouse where the bucket

is sitting on the ticking stove. In a shanty

of mirrors, I ladle steam over my shoulder —

the water is cut with salt and every little wound

sings: What is the Norwegian for download?

Dynamite

Bevan needed a place to winter-out. Son of a carpenter, resourceful to an almost comic degree, Elena took a liking to him — the ideal, the absurd. All manual jobs were his — problems of fish and fire and fowl. Just like Max, who became his understudy, Bevan was determined to take everything apart. The generator, the solar panels, the stove.

At the end of each day’s work, he jumped into the sea for a salt-water shock. Stars in the morning, stars in the evening. A folk tale of never-ending night.

From the pier to the lighthouse, one-hundred and thirty-nine steps. Fifteen times up and down equals two-thousand three-hundred feet of vert. I ran this, yoyo-style, many times a week. Max quoted me a time I never could beat.

When the sun finally returned, Elena brought him to the mainland where he was released like a bird. He cycled to the border with Russia. After a little rest he migrated south, meeting his father just outside of Tromsø. Bevan wanted to show Walt where he had wintered out. That’s why we’re headed to the mainland this morning.

§

A puffin struggles to take flight as we belly flop between the waves. Even in gloves, my fingers burn. Father and son are waiting for us on the pier at Steine. We load the bikes, the paniers, spare tyres.

Back on the island, everything is go. The old gangway — dashed in a storm — needs repair. Winches and pulleys are discussed — alternate strategies are sketched in the air. The whole thing must weight a tonne. The bolts are a flaking burning orange, like the stains below the scuppers of a ship. The I-beam (patented by the company of Forges de la providence — long-since bankrupt) cannot be trusted to hold. Max and Bevan converse about the likelihood — and consequence — of collapse.

§

Over tea, a story from the old days is told: a month after Bevan left, Elena decided that she wanted to deepen the bay; the outboard motor was snagging on the rocks at low-tide.

They gathered on the pier after the reef was seeded with dynamite.

Should we stand back?

It won’t be much!

An exclamation mark rose from the water and held for a moment before rocks and rubble came tumbling down.

§

The island is a bakery, a garage, a lab. The boys make muesli, motors and bread. A smooth white stone, a dinosaur egg, keeps the nozzle pressed on the stove.

Bevan studied Java programming before breakfast each morning. Art Ludwig’s Guide to Grey Water Run Off has coffee rings on the cover — it looks like a copy of the Principia.

Lime of the outhouse, seed of rhubarb wine — everything is a chance to run electricity through the algal bloom of our clowning. Eager for bubbling sap, we make homebrew to counter the monotony of tea. The kettle boils. I make another pot. All of creation is tired.

Slack Line Music

Pushed along by mist and rain,

I run past Per Anderson’s general store

or what remains of it. A few stone walls

behind the beach. Beams long since gone.

The village of Tarvågen has retreated

beyond the afterglow of creation.

§

Hitching from Lund, Max pushed thirty

kilograms of gear before him in a trolley.

He recalls: the jiu-jitsu champion of Sweden;

the man who tried to hang himself —

saved by the voice of the lord our god;

the famous petrol station where

they sold more buns than gasoline;

a caution from the police for hitching

on the slip-road of a motorway.

Meeting him two hours later, somewhere north

of Uppsala, they were impressed:

You travel fast, you and your trolley!

§

After work Julien sets up a slack line on the pier.

I sit beneath the rocks by the solar panels

as he balances over the page that I’m trying to read.

Arms rounding to an O above his head.

Reaching the ledge, he hops off and plucks the line.

If adventure has any kind of music

it is that note, puckered and improvised —

battered and plucked like a double bass.

§

It is late when I get back to the bucket

simmering on the stove.

Barbed Wire

Eyes! he shouts as a shard of glass whizzes

past my head. We’re digging out reams

and reams of old barbed wire; it’s double-helix,

prickledraad, in Dutch. Unwound, it stretches

from the island to the mainland and back again

Insert, delete, repair. The gods love torture,

open wounds. They glut themselves on despair.

But Julien is singing; pendulum pull — he drops

his axe and twists a chiral weakness. It snaps

in his hand like a rusty fish-head. We have bucket-

loads of the stuff. I trust his violence. The wire

is brittle as dried blood. I’m sure the gods hate him,

but they can go fuck themselves. They volunteered

to sit on their arse; he volunteered to work.

Si Phan Don

Every fast food restaurant longs for elsewhere.

I’m writing this from a kebab joint in Sortland

where the owner is watching cable news from

Istanbul on his laptop; he tells me he’s from

Alanya, former stronghold of the Ptolemaic

Seleucid, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman

Empires. There’s a painting of a river raft

on the wall — somewhere in China. By the window,

another painting — New England dusk and snow.

Eternally elsewhere, we rattle along the groove

of the world, a needle drifting into the vinyl

of the ocean, until we’re lifted up

and set down at the beginning of a memory,

a song: a church in Nyksund where a model ship

floats on plumb-line tackle, invisible, clear and strong.

A ghost ship. By the door, a double-helix leads

to a balcony where there is a ladder to another

room with a ladder to another song. I ring the bell.

It brings me to the Mekong — four thousand islands —

a riverine archipelago. On the far bank, a golden

Buddha, poorly lit. A radio crackles. Wind picks up.

Monks begin to scurry about the earth like ants

as the monastery percolates with rain as black as

coffee. A gong is rung. From my perch

I watch the dark where the river should be;

on the far horizon the tungsten flash of lightning.

Old photographer! Crack of incandescent bulb.

A sepia portrait clatters against the bamboo wall.

A curtain flutters by an open window. I’m worried

that it will crack and fall. The only glass is the glass

in the frame, and pressed against that glass,

the patriarch standing stiffly in a suit and tie —

colonial like Ataturk — pinned as a butterfly;

a dragon lurks in the silk of his daughter’s dress.

He longs to send her to Paris. Insists on speaking French.

Even in Laos, especially in Laos, they long

for somewhere else. In the morning, my notebook says:

Pineapple and coffee; blades of green tufted grass

in the water. I wonder if I can make it to the big island.

It’s not clear if this is a river or an ocean.

Four thousand islands. Si Phan Don. A creation myth.

I’m paddling hard though there is no sign of any current.

Laurence O’Dwyer holds a PhD in paradigms of memory formation from Trinity College Dublin. His first book of poetry, Tractography (Templar Poetry, 2018), received the Straid Collection Award. It includes his Poems from Haiti (Mudlark Flash No. 66, 2012) and Poems from Lapland (Mudlark Poster No. 140, 2016). He has another Mudlark Poster too, Poems from Litløy Fyr (No. 158, 2018). In 2018, he was a visiting scholar at the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of The Rensing Center (South Carolina). In 2017, he received a fellowship from The MacDowell Colony. In 2016, he won the Patrick Kavanagh Award for Poetry. He has also received a Hennessy New Irish Writing Award.

“Si Phan Don,” the last of the The Lighthouse Poems published here, received the Listowel (Co Kerry, Ireland) Writers’ Week Single Poem Prize (2019) and was published in an anthology produced by that festival.

Copyright © Mudlark 2019

Mudlark Flashes | Home Page