Daniel Becker

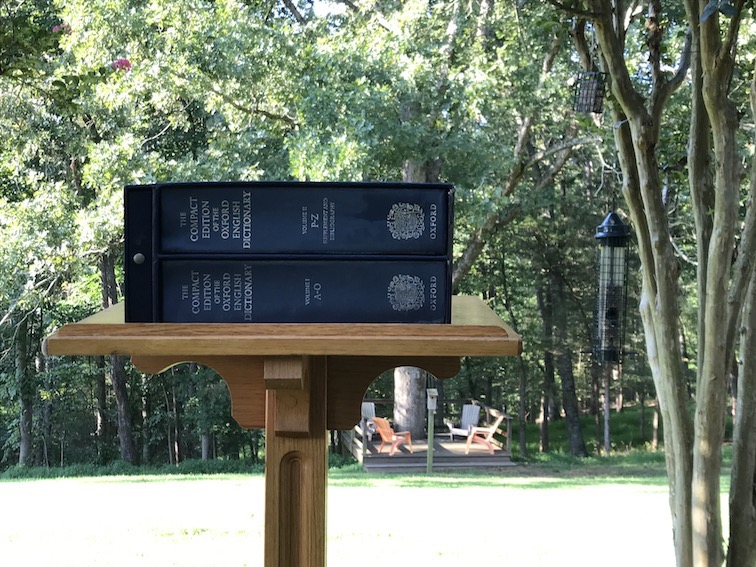

Photograph by Daniel Becker — Charlottesville, VA, 2020

Ode to the O.E.D.

Any phone call from any clinic patient

with any symptom that could be COVID

gets triaged to me.

Problem is, almost any symptom could be COVID,

and the more we learn the more we know

that half the time nothing could be COVID.

Maybe talking about it helps.

Meanwhile, I’m home and studying the birds at the birdfeeder

that hangs where I can see it while using a laptop

perched on a once proud lectern

that I rescued and rehabbed and put back to work

as a home for the forty-pound two volume version

of the Compact Oxford English Dictionary.

Its definitions need a hand-held magnifying glass

that comes in handy for getting tweezers on a deer tick

the size of a 20-font period.

The first use of the word pandemic was in 1628

when William Harvey mentioned plague—a pandemic

or endemic or highly prevalent disease—

while publishing his theory that blood circulates from veins to lungs

to heart to arteries to veins: purple to red to purple—

the circle of life.

It wouldn’t surprise Harvey to learn

it’s bad for the circulation to sit around all morning

hunched over a computer with an encrypted connection

to all the sad secrets inside the electronic medical record.

Standing up straight and marching in place to keep the blood flowing,

I notice the patient I need to call will need an interpreter.

The patient I need to call lives three hours away,

with misery to spare but no health insurance.

I was going to say “my heart sinks when I notice,”

but three times already this pandemic I look out the window

and notice a red headed woodpecker making my day

while pecking away at suet hung for that exact purpose.

Not a florid red, like a pink jogger

building up resistance to viral pneumonia,

nor the blush of embarrassment or anger,

but a deep hard-working non-glossy red, blood red,

arterial blood resting in the shade and catching its breath

on a not so great lung day.

Picture your lungs as a membrane two cells thick

but as wide and long as a football field

where, with ribs working as bellows,

oxygen enters and carbon-dioxide exits.

Picture your metabolism as an engine

that needs oxygen for power and mileage,

like the additive at the gas pump, the difference between

economy and premium, but in the case of oxygen

the difference between living and dying.

Picture the moment somewhere in Genesis

when the plain headed woodpecker

gets dipped in red ink up to its shoulders.

A blue headed woodpecker would also be of interest.

My mind wanders when waiting for triage phone calls.

Picture your un-slouched spine standing at the lectern

while you check out the crowded bird feeder

and take a deep breath before calling a frightened patient

who lives in one of those inconvenient crowded places

where poor people live without safe distance options.

Take another deep breath—breaths are still free—

before explaining via the interpreter

where a patient you’ve never met can go for help,

for a not quite free test, for vital signs with O2 sats,

for an exam by a doctor who manages to be welcoming

despite head to toe protective gear,

for labs and a chest x ray, for whatever it takes

to either know for sure or know enough to worry less.

It helps when the caller knows someone with a car,

a friend or relative without symptoms and not in quarantine,

someone willing and able to trade one good deed for another.

It helps when they have a map app on a cell phone

because directions get lost in translation

during the rush for reassurance. This live and let breathe reverie

is interrupted when a neighbor texts me a photo

of the rose-breasted grosbeak at her feeder,

the same neighbor who texts me a photo of her garden

and its bed of wild flowers, all volunteers

thanks to the well-fed song birds who visit.

The world is circling the drain, and I’m jealous of her bird seed.

Between patient phone calls I attend a video lecture

on migrating warbler plumage.

Warblers are often named for their colors,

and with that in mind there’s a linguistic aside

on the history of color names, when once upon a time

hue—light to dark—mattered more than pigment.

I got lost somewhere between “cerulean-blue” and “wine-dark” sea,

but why people with “red” hair actually have orange hair

made sense until I tried to explain it to my wife,

whose warbler learning curve is steeper than mine.

More than once she explains, as will the OED,

that prothonotary warblers are yellow

because the prothonotary clerk in a medieval court wore yellow.

Warblers are active in the rosy-fingered dawn,

and early in a pink sky in late April we’re on O Hill—

Observatory Hill, aka Mount Jefferson at Mr. Jefferson’s University—

for the spring warbler migration. They come up from Central America,

males first, looking for the right tree to build a nest

and start the next generation.

That description, except for the tree, applies to the last COVID phone call.

The Cerulean warbler stays near the sky at the top of the tree.

It sings poor, poor, pitiful me; poor, poor pitiful me.

Pitiful us to hear it and hear it and hear it and not see it.

Looking up in disappointment for too long

leads to warbler neck and the need to look into the eye level distance.

In front of our eyes and pain free to observe,

the observatory at the top of O Hill is 136 years old

and still getting to know its slice of the night sky.

The first floor is round and brick, buttressed every 10 feet.

Its domed second floor is strong proof that gravity is hard to resist.

The OED tells us that Keats, in 1820, a year before he died,

found himself “behind a portal buttressed by moonlight.”

I take a dictionary moment to see the heavens as Keats did,

to lean a moon beam where it does poetic

if not structural engineering good,

to compare his generations of tuberculosis to our first season of COVID.

His cough, like his mother’s and brother’s, was arterial red.

A year before he died he knew exactly how.

He could write about nightingales because they migrate

every spring from Africa to England.

They sang outside his window at night,

that tender night, and he put them to work.

Half a column of nightingale in the compact OED

says a lot about the focal plane of hand-held magnification

that flits from the history of a word

to the mystery of birdsong.

Outside my window, past the field and through the woods,

down the ravine and across the railroad,

on the road where rush hour no longer needs to rush,

sirens are coming and going.

Daniel Becker is Professor Emeritus of General Medicine at the University of Virginia School of Medcine. He has won the New Issues Press first book award, judged by Jericho Brown, for 2nd Chance which will be out in October 2020.

Copyright © Mudlark 2020

Mudlark Flashes | Home Page