Uses for Music

Poems by Annie Kim

from Eros, Unbroken

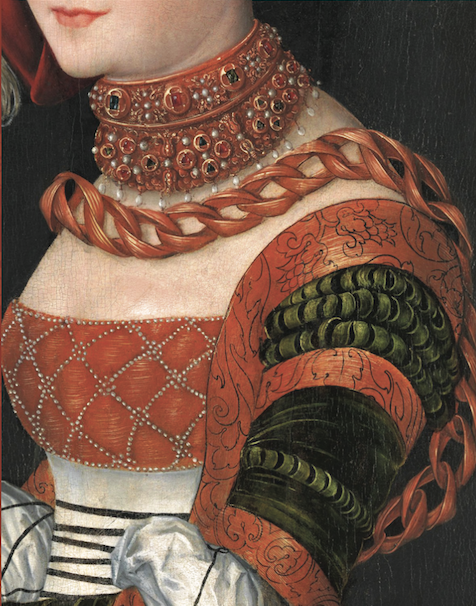

Detail from a Lucas Cranach painting of Judith and the Head of Holofornes,

ca. 1530, Oil on Linden, 35 1/4 in x 24 3/8 in

Author’s Note: Music was more than entertainment in the 18th century. Rulers like Queen Isabel Farnese of Spain believed that music had the power to cure. Young men who’d been castrated as boys to preserve their angelic voices dominated the stage. Queen Isabel convinced one castrato—an Italian born Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi, but known throughout Europe by his stage name, Farinelli—to come to Madrid to sing each night to her mentally unraveling husband, Philip V. There, Farinelli met his formidable counterpart and soon to be fast friend, Domenico Scarlatti. For decades, the two filled the court with opulent operas and hundreds of Scarlatti’s wildly intricate harpsichord sonatas. As a violinist and admirer of Scarlatti’s works, I became obsessed with the stories, both known and unknown, of these musician friends.

The book that emerged, Eros, Unbroken, includes imagined letters from Farinelli and dialogues between him and Scarlatti. These pieces form, if you will, the right hand line of a piano sonata. The left hand line—my own stories about love, music, and violence—weaves in and out throughout the book. I hope you’ll enjoy these lines that I composed from the music of these remarkable friends as much as I enjoyed writing them.

—AK

Contents

Confession | Uses for Music

Dear Riccardo (Madrid. Winter, 1727)

Dear Riccardo (Madrid. Spring, 1727)

Everything Swims | Fire Chasing Air

To Hold Something Close

Bright Skin of a Snake

Confession

The book in the library was yellow like the sun in a fraying tapestry. Titled simply: Domenico Scarlatti. I took it to an alcove, where morning light streamed in through the picture window, opened to the fly-leaf, and read.

. . . .

Story: a thing tangled up with something else. Eros: what tangles them.

. . . .

What I wanted on that clear summer morning was not biography, but passion. To dive like a small blue whale into the ocean. The hunt is rarely about the thing.

. . . .

Scarlatti: composer son of a famous composer, whose more than 550 keyboard sonatas, largely unpublished at his death in 1757, are the music of a divided self. Father. Gambler. Bankrupt.

Castrato: one who cuts his body to preserve his voice.

Farinelli: castrato singer, once the most celebrated in all of Europe, Scarlatti’s friend. Who quit the opera stage to sing each night to mad Philip V of Spain. Whose body, like Saint Sebastian’s in the Bernini sculpture that I love, twists even as it’s pierced.

. . . .

To be a thief you must love what you steal. I saw that I could write myself into their shadows. That I would need to pierce myself.

. . . .

Counterpoint: the art of building by pursuing more than one melodic line, each independent but connected.

Uses for Music

Because there is no soundtrack for the brain.

Because nothing has the beauty of a cage

you can enter when you want and leave behind.

So you can crawl across the floor and give it shape. So one day

you will release the snake—

you know, the one who lives inside you, has to move,

who can’t keep still.

— Madrid. Winter, 1727.

Dear Riccardo,

No time tonight to write

more than a scrap, dear Brother. You’re correct:

I leave for Madrid tomorrow. All is settled.

I’ve barely touched ground since leaving the Court.

She had the wildest eyes, the Spanish Queen—

clutching my hand, whispering in my ear

so others near us couldn’t hear, You must come.

Only the beauty of your voice can save Him.

Then tumbling from my lips, unaware, Yes.

I must be mad, Brother, as mad as he

to depart from this land for God knows what—

sitting here alone, all the dear old possessions

which made a life sinking into shadows.

I barely know the man writing these lines.

Your faithful Carlo

. . . .

All you’ve heard about El Escorial—

colossal, bare, full of drafts and sackcloth—

is, I’m afraid, true. We have no comforts,

unless you count stone and iron comforts.

I’ve never climbed up a damper stairwell.

Thank God the Court’s annual stay here

is brief. I can barely wait for winter,

when the whole palace flees to Aránjuez,

land of orange groves and plashing fountains.

It remains to be seen, Brother, what role

I create for myself at court. I have

my harpsichords, my books and paintings coming.

I can leave the palace at all hours

except when singing to the King. For now

that is enough. Picture me in good health,

as I will picture you, walking every night

beneath the shade trees in Father’s garden.

Send me the new aria you’ve written—

the one with the exiled prince in moonlight.

Give my best to Mother. Spare her details

you think would cause her suffering. My thoughts

and all my love I send across the ocean.

. . . .

A few lines more before I close this letter—

my nightly audience, you asked, how is he?

What can I say, Brother, in words alone?

He is a body crouched behind the curtains,

a hand mainly bones, the shuffle of linen.

He rasps and rocks and occasionally howls.

When he does, only an ancient servant,

one who nursed him as a boy, rushes in.

Only she can comfort him, good woman.

I do my part. What do you think I sing

but your own dear Ombra fedele anch’io?

‘Faithful shade,’ indeed. I stand in darkness

by the foot of a bed enclosed by drapes

so thick I think of dark confession boxes,

imagine something worse. Curtains opened

only a hand’s width: enough for one pair

of wolf’s eyes, hungry, yellow in the flame.

I sing of love, of course, and ships and sailors

pining for the shore—my voice oddly still

my voice.

There are nights when he barely breathes,

when his whole body strains to listen: I hear

his silence. And once, just once, after my last

held note, I heard his voice within the curtains—

Again. I want to hear that song again.

Your faithful Carlo

— Madrid. Spring, 1727.

Dear Riccardo,

You must not think me miserable. No, I am different here, I grow large and small all at once, a curious bird to the ladies who entreat me to sing. My voice belongs to my monarchs, I say, bowing. The Princess seeks me out: she has no love for gloom, all for music. Her music master—you will never guess— Domenico, the son of old Scarlatti. His hands are the fastest I’ve ever seen— a wonder he has broken no instruments. He plays like a tree being thrashed by a storm, wet and blind, I mean. And yet he sings. My deepest thanks again for Father’s desk. I can hardly tell you what joy it brings— the old knobs and grooves; to open its drawers. As I sit before it writing this letter many hours run back to me: another life. In both the old and the new, I remain, Your devoted Carlo

Everything Swims

—Farinelli and Scarlatti. Madrid, 1730s.

Too early for roses. Though even here— where sunlight barely touches any windows, the earth chokes with stones—every leaf turns green. “You should find yourself better company,” Scarlatti starts. “I’m not fit for the ladies, or,” casting a sideways glance at me, “fine men.” Those eyes like a pair of keen medallions, scarred but polished bright, flash across my body. Hedges high and thick on both sides of us— a thousand, ten thousand, shimmering leaves. Shadows on the gravel: his footsteps, mine. “You are a famous man. I do my best to be no one.” He kicks a stone in the air. We both watch it rise then drop, invisible. Time seems to flicker here, nearly blink. “Was a famous man might be more correct.” “Obscurity protects us, don’t you think? Vulcan, Prometheus, et cetera— they didn’t meet the happiest of fates. Here, in our little corner of the world,” Scarlatti taps the boxwood as he walks, “I thrive in the shadows like these hedges.” “There are many kinds of shadows, my friend.” What can I tell him of my nights? That fist rapping the post with its blind, raw knuckles? Taking off his hat, he wipes his forehead. “I heard a tune in the street the other day so old only the dead knew it. Sing it with me, maestro!” Clapping his thigh, he hums something Gaelic, wild, that only he would like, then turning, slaps me heartily on the shoulder. I laugh. What else can I do? I sing, picking out a few, clear notes above his, that baritone a cracked bronze bell, burnt sugar on the tongue. The sun is climbing higher in the sky: I remove my hat. Relentless, this spring. / / “What do you remember about your father?” Scarlatti’s voice emerges from his chair. Past midnight, portraits of the royal family staring down at us from walls, candle-lit— high, lonely faces, white as altar marbles. I raise my glass to them in a silent toast. “Everything strong and good, I suppose. Decent. A loving husband, father, able composer. And you? What made you think of this just now?” “The same of course. Oh, the man was perfect. Imagine, his mind is a library, his hands”— opening his, strong hands for octaves, tenths— “two banks of the vast ocean. Inside them everything swims, including you.” He wipes his lips. “Why, then, don’t you want to write an opera? You wrote many operas as a young man,” I continue, leaning in, “like your father.” “And have you heard these fine works? Enough world, my friend, exists already. Look around you. Why create false ones with gods and heroes? You were young, I think, when your father died?” I slosh the wine in my glass. Strange how separate a thing can feel, even in your hand. You’ll never be it. “Not so young.” “You premiered in London practically a child, that I know. By twenty, I would guess, you’d made all the money you could want from the stage.” I take a long sip. “Of the things he loved, independence was what he loved the best. My father wanted his sons to owe no one.” “Splendid. You’ve done exactly what he wished. I suppose, dear musico, I am jealous. I suppose I could have lived a different life, spent my energies differently, not squandered—” Lost in some reflection, he grows silent.

Fire Chasing Air

— Farinelli and Scarlatti. Madrid, 1740s.

“How immaculate your life seems to me.”

Scarlatti stares at the white domed ceiling—

Orpheus sprawled against a grassy bank,

finger pointing grandly at the blank sky.

“The clean lines of your mind, its every wish,”

he nods at the pen in my hand, “transforming

into act. Never a doubt, not a wisp

of smoke in the chimney. A life like that—”

Scarlatti sinks into my couch, arms flung

across the slender mahogany back.

Laughing, I look up from my desk. Father’s:

thick, blotted papers, some crinkling with heat.

I lay down my pen. The ink must dry.

He laughs, rubbing his eyes, staring out now

through the windows behind me at the park:

a still May morning, hedges half in shadow.

“How is the Scarlatti household these days?

The young Scarlattis and their mother well?”

“Yes, yes.” Crossing to my table, he picks up,

puts down, first a Chinese fan, then a rock—

glass-smooth, black as a canal in Venice.

“How much pressure, do you think, did it take

to make this small stone smooth? How many years?

Fire chasing air. I used to think this thing, this

pressure, was desire. I was a young man.

It was all one soul chasing another—.

Then I thought it was my daimon: a voice

singing to me through the windows, late at night,

lovely in its own way, taunting me, of course.”

He stares intently at the polished stone.

“A thing that’s named can be called, can it not?

And if it’s called, will it not come?”

Behind me I can hear the sounds of mowing,

swish of insect wings above high grass blades—

it’s the time of year I love most, hate most,

when even the morning air swells with longing.

“Sogno o vaneggio?” I sing the line.

He looks at me, a little smile on his lips.

“Is it a ‘dream’ or a ‘mirror’?... Indeed. Orfeo.

Memory serves you well, my friend.

Though you do not ask, nor do I tell you

what flits beneath the surface of this glass.

Perhaps,” he turns the stone between his fingers,

“I fear to dent that smooth sail of your mind,

the singularity of purpose you enjoy from

a life so”—he pauses—“unconstrained.”

I flinch. “Nothing is that simple.”

I see the papers on my desk—all the same,

all the writing in my hand neat, ordained.

“Of course.” He lays the stone back in its place,

tip of one finger hesitating still.

“I understand you paid my bills in town.

I did not dream—”

I wave my hand to stop him.

“Nothing should be owed between...true friends.”

“I am grateful.” Hands in his pockets now,

a sly smile pulls the corners of his mouth.

“My daimon thanks you, whatever his name.”

To Hold Something Close

— Farinelli and Scarlatti. Aránjuez, 1740s.

“So she will not come here,” speaks Scarlatti slowly. “This woman who adores you, I can see, whom you respect as you respect few people.” Back against an old beech tree, Scarlatti leans. Behind us, men crossing the stage, hands full— silk vines, screens painted with the moon and stars, a pair of satin cloaks with ermine hems, a long blue feather trailing from a hat. “You must see that I’m not young anymore. What you ask me to do is impossible.” “But you’re not old, not by Nature’s standards. A ridge in this trunk”—he taps—“a sapling.” “Of all people, I thought you’d understand what a man must do sometimes for freedom. But the matter’s done. I’ve sent my reply. I would not have forced all of this on you— you can’t imagine how I hate it—but I needed, wanted, to explain my silence.” Silver beneath the leaves, his eyes flicker. “Dear musico, I’ve known you for too long— I know how the walls of your building lean, where the wind blows in, sun strikes its windows. She won’t come here because you refuse to be—” he bends, plucking a fresh twig from the grass, two or three green leaves still attached—“taken.” Reaching for my hand, he turns it palm-up, lays the twig upon it, shuts my fingers. “This is how it feels to hold something close.”

Bright Skin of a Snake

— Farinelli and Scarlatti. Aránjuez, 1750s.

“Your library is a model of order,” I say, slipping off my gloves, folding them. Walls of books, a few abandoned, tattered chairs, one window propped half-open by a stick. First breeze of summer evening drifting in. The writing table where he sits, quickly copying, fills most of the cluttered room, wood black, all sides and corners— “An octagon,” he says, still scribbling. “After the eight wind gods of ancient Greece. Or some such. It’s neither square nor circle, though a little of both—that’s what I like. But I assume it’s not your love of geometry to which I owe the honor of this visit?” He looks up at me, his eyes red and damp. “The only wind I remember is Hebrides. But no, I didn’t come for geometry, though I like this table: it suits you. No,” I sit, choosing the chair closest to me, “I haven’t seen you all week. I feared you weren’t well, though Signora told me you are quite yourself.” I glance at the table: manuscripts, six, seven piles arranged in stacks—fair copies. “Myself.” He smiles. “I am always myself. Strange, don’t you think, how much that little word ropes off the world as we know it? As if,” he leans back, looking up at the ceiling, row after row of beams crossing the plaster, “all our lives we ran only in parallel, we never once pierced the skin of ourselves.” Laying down his pen, he rubs his eyes. “So we are to speak of geometry?” From the armrest one stray thread unfurls— waving, colorless, mute. Easy to pull. “Then I come to you, friend, as one of your unpierced, parallel lives. Call me a line marching forward since the day I left school—” words tumble from my mouth, too quick, too much— “I’ve taken pride in this—how shall I say?— seamlessness. I am the infinite straight line. And where has it brought me?” Scarlatti leans back in his chair, shuts his eyes. “When my father died, I was already forty. Not a young man. I had been, as you’ve been, wonderfully gifted with regularity. With his death,” he breathes deeply, “something fell, dropped away—do you remember that tale? Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus, blinded by the mighty hand of God three days. Once he believed, the Lord unblinded him.” He opens his own. “Then something like scales fell from his eyes. That’s how I felt. As if in my hand lay the foiled bright skin of a snake, newly sloughed, suddenly thin and weightless. As if to say, you may now stop caring. I say this because I have seen both sides— life before and after that ‘marching line’— seen that I’m as likely to charm and disappoint no matter what I say, what I do. You’re different. You’re like a garden everyone goes to for calm and beauty. You will always bloom.” Something like tears—no, actual tears— fill my eyes, threaten to betray themselves. “Odd to hear, since you don’t care for gardens.” Out the window, the fields are growing dark. “That’s not true—it’s not that I dislike gardens. I dislike the life kept out of gardens, all the weeds and overgrowth deemed unfit. Though you’re not one of those gardens, are you?” I laugh. “If you mean that I am full of weeds, you’re correct. Though you surprise me, maestro, to suggest that you are less than blooming”” I point to the papers beneath his pen. “Oh, the sonatas!” He laughs or sighs. Both. “Yes, they are a given. I must write them. Not made for heavy burdens, as you know, but I have no choice but to love them despite, or because of, their lightness.” He looks down. “They are, anyhow, all that I have done.” We sit silent a moment. Night has come, hay and wild honeysuckle threading the air. Eventually he stirs himself and stands, lights candles on the table, calls for wine. I don’t remember what we talked of next— some long, amusing tale about his gardener or the new French envoy—we talked, we drank. I remember leaning back, head swimming, thinking this, this, I will always want this.

Annie Kim is the author of Into the Cyclorama, winner of the Michael Waters Poetry Prize, and Eros, Unbroken, winner of the Washington Poetry Prize. Kim’s work has appeared in journals such as The Kenyon Review, Cincinnati Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Plume and Narrative. She works as an assistant dean at the University of Virginia School of Law, teaches poetry and legal writing, and writes micro book reviews for DMQ Review. You can find out more about Annie Kim and her work by visiting her webpage: anniekim.net.

Other poems by Annie Kim in Mudlark can be found here: Night at the Cyclorama, Flash No. 91 (2014).

Copyright © Mudlark 2020

Mudlark | Home Page